The Standard Guideline for Rural Housing in Disaster Prone Areas of Bangladesh has been developed by the Housing and Building Research Institute (HBRI), in association with the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief and the Department of Disaster Management (DDM), in collaboration with Friendship and the Shelter Research Unit of International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). The aim of formulating this guideline is to assist both the housing facilitators and end users living in extreme natural conditions.

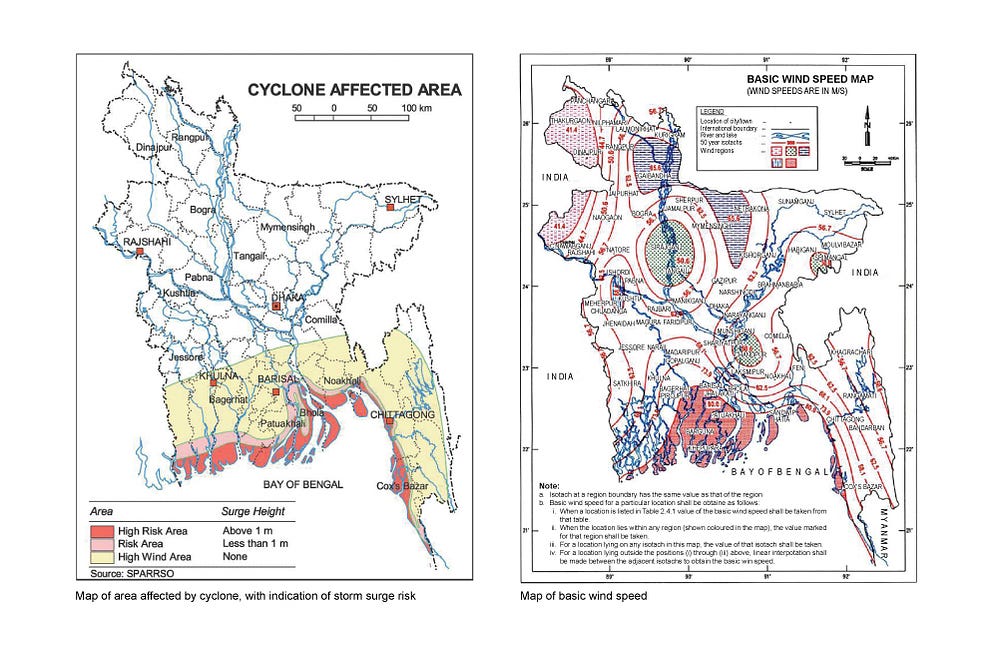

Bangladesh being a low-lying deltaic plain, it is particularly susceptible to many extreme climatic phenomenon due to its geographic location and meteorological factors. It is often cited as one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, due to climate change and rising ocean levels. Bangladesh’s population, particularly in the underdeveloped rural areas have been adversely affected by these issues for generations, and the infrastructure as it stands is limited by the environment and resources available to the impoverished, uneducated populace and the lack of awareness and technical knowhow regarding the construction of these buildings; consequently suffering from significant inadequacies.

Although Bangladesh has shown responsive approaches to disaster risk reduction and management, the lack of an inclusive policy and guideline at national level was obstructing the successful outcome of the overall process in most cases. In order to address the greater need of the nation, a strong demand has been felt to formulate a national guideline and design manual for rural areas especially prone to natural extremities.

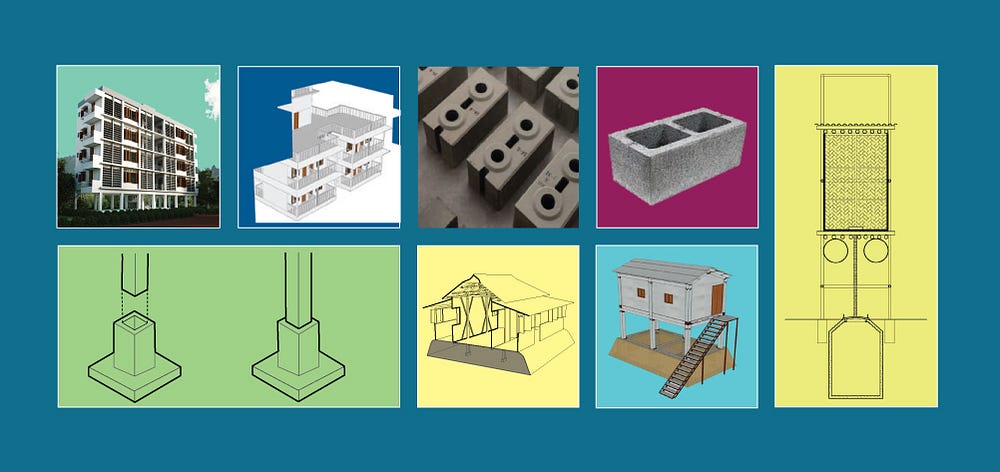

Housing is of course one of the highest priorities in the government’s agenda, and as such the primary objective of the Housing and Building Research Institute (HBRI) is to promote sustainable building materials and construction techniques for both rural and urban housing with the aim of reducing the risks associated with natural calamities. However, a wide-spread, standardized, robust and comprehensive approach towards a long-term, sustainable solution was easier said than done.

An intensive research was conducted considering monsoons, cyclones, floods, extreme weather and landslides, having reviewed already existing resources and visited many affected places to learn about the existing qualitative housing designs for various disaster types as well as the material, culture and techniques prevalent in Bangladesh.

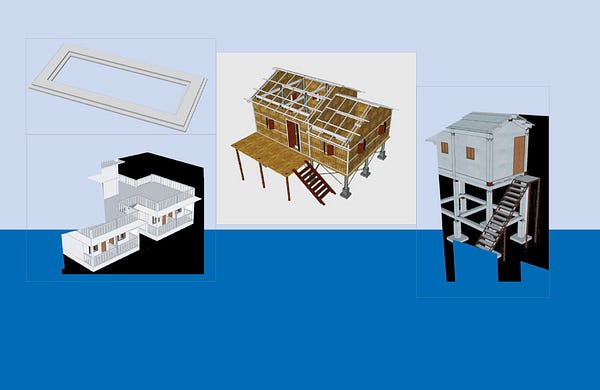

The guideline advocates the idea that a more optimal use of these resources is not only possible, but is the best strategy to realize a substantial improvement of the rural housing of Bangladesh, as it combines the best of traditional design and methodology as well as the newly developed designs in a systematic, viable and pragmatic manner.

Therefore, the guideline solicited all types of relevant skills and knowledge; included a variety of local and newly introduced materials; presented strategies for an optimal quality-cost balance; is sensitive to issues of land security; and lastly is an important tool to promote and facilitate coordination around rural housing. This approach will work towards reducing the impact of future disasters on the rural housing of Bangladesh and building a greater resilience through pre-emptive measures that considers all the logistical and engineering factors relevant to the areas they will serve.

The guideline was developed with the financial contribution of the Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Directorate for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs.

Download Guideline Here